Biodiversitätserhebungen in Kräuteranbauflächen

Abstract

Medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) in mountain regions are cultivated on small-scale farms, which are characterized by a great diversity of MAPs grown on a relatively small area and by a high degree of habitat complexity. Non-crop elements (e.g., dry-stone walls, hedges, etc.) are widely present in these cultivated areas and, together with high plant diversity, may provide ideal foraging and breeding habitats for several animal groups. Here we surveyed small-scale MAP fields from a multi-taxonomic perspective considering flower-visiting arthropods, butterflies, grasshoppers, ground-dwelling arthropods, birds, and bats. A total of three MAP fields were surveyed, however not every taxon was surveyed in each MAP field. Pan traps were used in all MAP fields to assess flower-visiting arthropods with special attention to wild bees. In one of the selected fields a Malaise trap was used, and the other taxa were surveyed according to the protocol of the Biodiversity Monitoring South Tyrol. An exception was the bird surveys, which were conducted in two MAP fields. Our results indicate MAP fields to be a valuable habitat for several taxa, especially wild bees, as reflected in the positive correlation of wild bee species richness and flower coverage. Next to beneficial arthropods, potential pests such as aphids were also highly abundant. However, natural enemies (e.g., hymenopteran parasitoids, ground-dwelling predators, etc.) were also numerous and possibly counteracted pests. The butterfly and grasshopper fauna were represented by common and generalist species, while the observed vertebrate communities were relatively diverse in their habitat requirements, most likely using MAP fields for foraging. Overall, we conclude that MAP cultivation sites may act as resource-rich oases for several animal groups, thereby also promoting biodiversity on a broader scale.

Arznei- und Gewürzpflanzen werden in Bergregionen in kleinen Kräuteranbau-Betrieben, die sich durch eine hohe Pflanzen- und Strukturvielfalt (Trockenmauern, Hecken, usw.) auszeichnen, angebaut. In dieser Studie wurden Kräuteranbau-Betriebe als Lebensraum für verschiedene Tiergruppen untersucht, wobei blütenbesuchende Arthropoden (Wildbienen, Bock- und Prachtkäfer), Schmetterlinge, Heuschrecken, bodenoberflächen-aktive Arthropoden, Vögel und Fledermäuse berücksichtigt wurden. Die Kräuteranbau-Betriebe stellten sich als ein wertvoller Lebensraum für verschiedene Tiergruppen heraus, die möglicherweise die Flächen als Nahrungs- oder auch als Bruthabitat nutzen. Insbesondere Wildbienen waren mit 10% des regionalen Artenpools besonders zahlreich und reagierten positiv auf das Vorkommen von Blüten. Neben nützlichen Arthropoden waren auch potenzielle Schädlinge sehr häufig anzutreffen, wobei natürliche Feinde, wie Räuber und Parasitoide, ebenfalls zahlreich vertreten waren. Die Schmetterlings- und Heuschreckenfauna war durch häufige und generalistische Arten vertreten, während Vögel und Fledermäuse sich durch verschiedene Lebensraum- und Landschaftsansprüche auszeichneten. Insgesamt können Kräuteranbau-Betriebe in der Agrarlandschaft als ressourcen- und strukturreiche Oasen für verschiedene Tiergruppen fungieren und sich somit womöglich auch positiv auf die Biodiversität auf einer breiteren Skala auswirken.

Le erbe medicinali ed aromatiche nelle regioni montane vengono coltivate in piccole aziende agricole. Queste sono caratterizzate da un'elevata diversità di piante coltivate e da un elevato grado di complessità della struttura dell’habitat dovuta alla presenza di elementi naturali e semi-naturali non colturali (es. muri a secco, siepi, ecc.). In questo studio sono stati analizzati alcuni gruppi di animali presenti in tre campi di erbe medicinali e aromatiche differenti. Nello specifico sono stati rilevati insetti visitatori di fiori (api selvatiche, cerambicidi e buprestidi), farfalle diurne, cavallette, artropodi della superficie del suolo, uccelli e pipistrelli. I risultati indicano che i campi di erbe medicinali ed aromatiche sono un habitat prezioso per diversi taxa, i quali usano questo ambiente per l'alimentazione o per la riproduzione. I campi di erbe sono soprattutto importanti per le api selvatiche, come dimostra la correlazione positiva tra la ricchezza di specie di api selvatiche e la percentuale di copertura floreale. Inoltre, sono state rilevate circa il 10% delle specie di api selvatiche presenti nella provincia, ciò evidenzia che questi habitat sono particolarmente ricchi di specie. Oltre agli insetti impollinatori, anche insetti potenzialmente dannosi per l’agricoltura, come gli afidi, e insetti antagonisti naturali come predatori e parassitoidi sono risultati abbondanti. Le comunità di farfalle e cavallette sono caratterizzate da specie comuni e generaliste, mentre per gli uccelli e pipistrelli sono state rilevate specie esigenti per qualità di habitat e paesaggio che probabilmente utilizzano i campi di erbe per il foraggiamento. Nel complesso, i campi di erbe medicinali ed aromatiche possono fungere nell’ambiente agricolo da oasi ricche di risorse e strutture naturali per diversi gruppi di animali, promuovendo un alto valore di biodiversità anche ad una scala più ampia.

Introduction

- [1] Máthé Á. (2015). Utilization/Significance of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. In: Máthé Á (ed.). Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of the World. Scientific, Production, Commercial and Utilization Aspects. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany, here pp. 1-12, DOI: 10.1007/978-94-017-9810-5.

- [2] Ahad B., Shahri W., Rasool H. et al. (2021). Medicinal Plants and Herbal Drugs. An Overview. In: Aftab T., Hakeem K.R. (eds.). Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Healthcare and Industrial Applications. Springer, Cham, Switzerland, here p. 2, DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-58975-2_1.

- [3] Lubbe A., Verpoorte R. (2011). Cultivation of medicinal and aromatic plants for specialty industrial materials. Industrial Crops and Products 34 (1), 785-801, DOI: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2011.01.019.

- [4] Leaman D.J. (2008). Conservation and Sustainable Use of Wild-sourced Botanicals. Planta Medica, 74, 11, DOI: 10.1055/s-2008-1075152.

- [5] Shippmann U., Leaman D.J., Cunningham A.B. (2002). Impact of Cultivation and Gathering of Medicinal Plants on Biodiversity. Global Trends and Issues. In: Biodiversity and the Ecosystem Approach in Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Satellite event on the occasion of the Ninth Regular Session of the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, Rome, Italy, October 12-13, 2002. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

- [6] Salomon I., Haban M., Otepka P. et al. (2018). Perspectives of small- and large- scale cultivation of medicinal, aromatic and spice plants in Slovakia. Medicinal Plants 10 (4), 261-267, DOI: 10.5958/0975-6892.2018.00041.2.

- [7] Allen D., Bilz M., Leaman D.J. et al. (2014). European Red List of Medicinal Plants. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, Luxembourg, here p. 4.

- [8] Südtiroler Bauernbund (ed.) (2014). Nischenkulturen als Erwerbsmöglichkeit. Chance und Herausforderung für die Südtiroler Landwirtschaft. Südtiroler Bauernbund, Bozen/Bolzano, Italy. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://issuu.com/effektgmbh/docs/sbb_broschu__re_nischenkulturen.

- [9] Šálek M., Hula V., Kipson M. et al. (2018). Bringing diversity back to agriculture. Smaller fields and non-crop elements enhance biodiversity in intensively managed arable farmlands. Ecological Indicators 90, 65-73, DOI: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.03.001.

- [10] Licata M., Maggio A.M., La Bella S. et al. (2022). Medicinal and aromatic plants in agricultural research, when considering criteria of multifunctionality and sustainability. Agriculture 12 (4), 529, DOI: 10.3390/agriculture12040529.

- [11] Hoppe B. (ed.) (2007). Handbuch des Arznei- und Gewürzpflanzenanbaus. Bd. 3: Krankheiten und Schädigungen an Arznei- und Gewürzpflanzen. SALUPLANTA e. V., Bernburg, Germany.

- [12] Pramsohler M., Gallmetzer A., Castellan A. et al. (2022). Erster Nachweis und molekularbiologische Bestimmung von Donus intermedius (Coleoptera: Curculionoidae) als Schädling bei Zitronenmelisse in Südtirol. Laimburg Journal 4, DOI: 10.23796/LJ/2022.003.

- [13] Nickel H., Blum H., Jung K. (2014). Verbreitung und Biologie der an mitteleuropäischen Arznei- und Gewürzpflanzen schädlichen Blattzikaden (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae, Typhlocybinae). Cicadina 14, 13-42, DOI: 10.25673/92235.

- [14] Meyer U., Blum H., Gärber U. et al. (2010). Praxisleitfaden Krankheiten und Schädlinge im Arznei- und Gewürzpflanzenanbau. Julius-Kühn-Institut Selbstverlag, Braunschweig, Germany.

- [15] Pobożniak M., Sobolewska A. (2011). Biodiversity of thrips species (Thysanoptera) on flowering herbs in Cracow, Poland. Journal of Plant Protection Research 51 (4), 393-398, DOI: 10.2478/v10045-011-0064-2.

- [16] Gupta S.K., Karmakar K. (2011). Diversity of mites (Acari) on medicinal and aromatic plants in India. Zoosymposia 6, 56-61, DOI: 10.11646/zoosymposia.6.1.10.

- [17] Venkatesh Y.N., Neethu T., Ashajyothi M. et al. (2022). Pollinator activity and their role on seed set of medicinal and aromatic Lamiaceae plants. Journal of Apicultural Research, Vol. ahead-of-print, DOI: 10.1080/00218839.2022.2080949.

- [18] Kumari B., Ravinder R. (2017). Pollination studies in Tagetes minuta, an important medicinal and aromatic plant. Medicinal Plants – International Journal of Phytomedicines and Related Industries 9 (2), 140-142, DOI: 10.5958/0975-6892.2017.00021.1.

Methods

Research area and study sites

- [19] Hilpold A., Anderle M., Guariento E. et al. (2023). Handbook - Biodiversity Monitoring South Tyrol. Eurac Research, Bolzano, Italy, DOI: 10.57749/2qm9-fq40.

Data collection

Pan traps

- [20] Vrdoljak S.M., Samways M.J. (2010). Optimising coloured pan traps to survey flower visiting insects. Journal of Insect Conservation 16, 345-354, DOI: 10.1007/s10841-011-9420-9.

- [21] Droege S., Tepedino V.J., Lebuhn G. et al. (2010). Spatial patterns of bee captures in North American bowl trapping surveys. Insect Conservation and Diversity 3 (1), 15-23, DOI: 10.1111/j.1752-4598.2009.00074.x.

- [22] Goulet H., Huber J.T. (eds.) (1993). Hymenoptera of the world. An identification guide to families. Canada Communication Group, Ottawa, Canada, here pp. 65-529.

Additional surveys

In M, Malaise traps were installed three times for five consecutive days from mid-June to late August. Collecting bottles were filled with 70% ethanol and transferred to fresh ethanol until further processing. Sorting and identification of arthropods was performed by LO following the same procedure as the PT sorting and identification.

- [19] Hilpold A., Anderle M., Guariento E. et al. (2023). Handbook - Biodiversity Monitoring South Tyrol. Eurac Research, Bolzano, Italy, DOI: 10.57749/2qm9-fq40.

- [23] Bibby C.J., Burgess N.D., Hillis D.M. et al. (2000). Bird census techniques. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom, here pp. 91-112.

- [24] Anderle M., Paniccia C., Brambilla M. et al. (2022). The contribution of landscape features, climate and topography in shaping taxonomical and functional diversity of avian communities in a heterogeneous Alpine region. Oecologia, 199, 499-512, DOI: 10.1007/s00442-022-05134-7.

- [25] Fornasari L., Mingozzi T. (1999). Monitoraggio dell'avifauna nidificante in Italia. Un progetto pluriennale sulle specie comuni. Avocetta - Journal of Ornithology, 23, 153-153.

- [26] Barataud M. (2015). Acoustic ecology of European bats. Species Identification and Studies of Their Habitats and Foraging Behaviour. Biotope & National Museum of Natural History, Paris, France, here pp. 104-263.

- [27] Teets K.D., Loeb S.C., Jachowski D.S. (2019). Detection probability of bats using active versus passive monitoring. Acta Chiropterologica 21 (1), 205-213, DOI: 10.3161/15081109ACC2019.21.1.017.

- [28] Hilpold A., Kirschner P., Dengler J. (2020). Proposal of a standardized EDGG surveying methodology for orthopteroid insects. Palaearctic Grasslands 46, 52-57, DOI: 10.21570/EDGG.PG.46.52-57.

- [29] Guariento E., Rüdisser J., Fiedler K. et al. (2022). From diverse to simple: butterfly communities erode from extensive grasslands to intensively used farmland and urban areas. Biodiversity and Conservation 32, 867-882, DOI: 10.1007/s10531-022-02498-3.

Ground-dwelling macro-invertebrates were collected with pitfall traps by JP. A glass jar with a diameter of 7.5 cm and a height of 9 cm was filled with 200 ml 75% propylene glycol. The traps were protected from rain and other disturbances by a polycarbonate Lexan® roof. Two traps per survey period were set, once in early summer and once in autumn, resulting in a total of four traps exposed for 15 days each.

Analysis

- [30] Hsieh T.C., Ma K.H., Chao A. (2016). iNEXT: an R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers). Methods of Ecology and Evolution 7 (12), 1451-1456, DOI: 10.1111/2041-210X.12613.

Results

Medicinal and aromatic plants around the pan traps

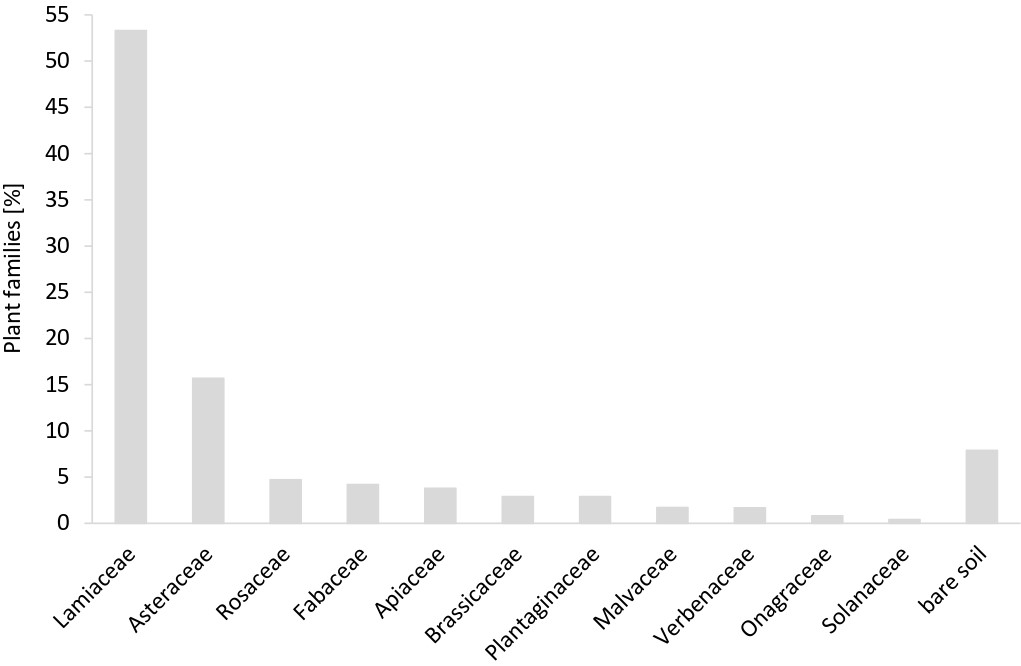

A total of 38 species and two genera of medicinal and aromatic plants (MAP) from 11 different plant families were recorded around the pan traps (PT) (Fig. 2). In Merano/Meran (M) and Prati/Wiesen (W), 17 MAP species were recorded each, and 21 recorded in Castelrotto/Kastelruth (K). The MAP species, which accounted for 50% of the cover around the PT, were Mentha sp. (12.4%), Monarda didyma L. (10.7%), Lavandula angustifolia (8.6%), Thymus citriodorus (Pers.) Schreb. (8.6%), Nepeta cataria L. (6.5%), and Calendula officinalis L. (5.3%). The MAP species recorded in each MAP field are listed in Table 1.

Fig. 2: Percentage of medicinal and aromatic plant families recorded in quadrats of 5 x 5 m around each pan trap set.

Tab. 1: Species list of the medicinal and aromatic plant (MAP) species recorded around the pan traps per MAP field (M = Merano/Meran, K = Kastelruth/Castelrotto, W = Wiesen/Prati). The number 1 represents the presence of the MAP in the respective MAP field.

Taxa |

M |

K |

W |

|---|---|---|---|

Achillea millefolium L. |

|

1 |

|

Agastache anethiodora (Nutt.) Britton |

|

1 |

|

Alcea rosea L. |

1 |

|

|

Alchemilla vulgaris L. |

1 |

1 |

|

Althaea officinalis L. |

1 |

|

|

Arnica montana L. |

1 |

|

|

Artemisia dracunculus L. |

|

1 |

|

Calendula officinalis L. |

1 |

1 |

1 |

Carumcarvi L. |

|

1 |

|

Centaurea cyanus L. |

1 |

1 |

1 |

Coriandrum sativum L. |

|

1 |

|

Dracocephalum moldavica L. |

|

1 |

|

Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench |

|

1 |

|

Echinacea sp. |

1 |

|

|

Fagopyrum esculentum Moench. |

|

1 |

|

Hyssopus officinalis L. |

|

1 |

|

Lavandula angustifolia MILL. |

1 |

1 |

|

Leontopodium alpinum Cass. |

|

1 |

|

Malva sylvestris L. |

1 |

1 |

|

Matricaria chamomilla L. |

1 |

|

|

Melissa officinalis L. |

1 |

1 |

1 |

Mentha sp. |

|

1 |

1 |

Mentha spicata L. |

|

1 |

|

Monarda didyma L. |

1 |

1 |

1 |

Monarda fistulosa L. |

|

1 |

|

Nepeta cataria L. |

|

1 |

1 |

Ocimum basilicum L. |

1 |

|

|

Oenothera biennis L. |

|

1 |

|

Origanum majoran L. |

|

1 |

|

Origanum vulgare L. |

|

1 |

|

Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss |

1 |

|

|

Plantago lanceolata L. |

|

1 |

|

Sanguisorba minor Scop. |

1 |

|

|

Satureja montana L. |

|

1 |

|

Sinapis alba/Raphanus sativus |

1 |

|

|

Solanum tuberosum L. |

|

1 |

|

Thymus citriodorus (Pers.) Schreb. |

1 |

1 |

|

Trigonella caerulea L. |

|

1 |

|

Urtica dioica L. |

|

1 |

|

Verbena officinalis L. |

|

1 |

|

Veronica sp. |

|

1 |

|

Species richness |

17 |

21 |

17 |

Pan traps

Overall, 12 570 arthropods were collected with PT, of which 12 155 were considered target taxa attracted by the colors of the PT (flower visiting Coleoptera, Diptera, Hymenoptera, Thysanoptera, Lepidoptera, Sternorrhyncha). An average of 4051.7 ± 684.7 target taxa were recorded per MAP field. The total abundance and average abundance of each taxon per MAP field is listed in Table 2.

Tab. 2: Abundance of taxa recorded with Malaise traps (MT) in Merano/Meran (M) and with pan traps (PT) in each medicinal and aromatic plant field (MAP) (M, K = Castelrotto/Kastelruth, W = Prati/Wiesen). Taxa recorded with PT are divided into target taxa of PT and non-target taxa of PT. For W, values with (+ PT B) and without (- PT B) the additional pan trap set are indicated. Average abundance (± SD) per MAP field and taxon were calculated with M, K, and W (- PT B).

Taxa |

MT |

PT |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Abundance |

Abundance |

M |

K |

W |

W |

Average (± SD)/MAP field |

||

(- PT B) |

(+ PT B) |

|||||||

Target taxa of PT |

Coleoptera varia |

102 |

524 |

247 |

188 |

89 |

101 |

174.7 (SD ± 79.8) |

Buprestidae |

89 |

12 |

53 |

24 |

28 |

29.7 (SD ± 21.1) |

||

Cerambycidae |

2 |

29 |

4 |

5 |

20 |

25 |

9.7 (SD ± 9) |

|

Curculionidae |

14 |

7 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2.3 (SD ± 2.3) |

|

Diptera varia |

1004 |

7585 |

1303 |

2686 |

3596 |

4259 |

2528.3 (SD ± 1154.6) |

|

Syrphidae |

21 |

222 |

28 |

155 |

39 |

54 |

74 (SD ± 70.4) |

|

Parasitoids/Cynipoidea |

514 |

334 |

123 |

138 |

73 |

90 |

111.3 (SD ±34) |

|

Wild bees |

20 |

235 |

67 |

91 |

77 |

81 |

78.3 (SD ± 12.1) |

|

Apis mellifera |

2 |

151 |

74 |

57 |

20 |

30 |

50.3 (SD ± 27.6) |

|

Symphyta |

11 |

100 |

4 |

16 |

80 |

101 |

33.3 (SD ± 40.9) |

|

Vespoidea/Spheciformes |

31 |

86 |

29 |

14 |

43 |

52 |

28.7 (SD ± 14.5) |

|

Sternorrhyncha |

249 |

793 |

409 |

255 |

129 |

155 |

264.3 (SD ± 140.2) |

|

Thysanoptera |

6 |

1977 |

951 |

776 |

250 |

320 |

659 (SD ± 364.9) |

|

Lepidoptera |

86 |

23 |

5 |

8 |

10 |

12 |

7.7 (SD ± 2.5) |

|

Non-target taxa of PT |

Acari |

14 |

206 |

34 |

53 |

119 |

170 |

68.7 (SD ± 44.6) |

Heteroptera |

15 |

70 |

22 |

41 |

7 |

7 |

23.3 (SD ± 17) |

|

Auchenorrhyncha |

74 |

63 |

23 |

19 |

21 |

24 |

21 (SD ± 2) |

|

Collembola |

28 |

32 |

3 |

17 |

12 |

12 |

10.7 (SD ± 7.1) |

|

Formicidae |

82 |

23 |

17 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

7.7 (SD ± 8.3) |

|

Araneae/Opiliones |

|

10 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

3.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

|

Mecoptera |

2 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

1.3 (SD ± 1.5) |

||

Dermaptera |

5 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 (SD ± 1) |

||

Psocoptera |

2 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 (SD ± 1) |

||

Orthoptera |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0.33 (SD ± 0.6) |

|||

Trichoptea |

2 |

|

|

|||||

Raphidioptera |

1 |

|

|

|||||

Total Abundance |

2289 |

12570 |

3366 |

4583 |

4621 |

5537 |

||

Abundance of target taxa (PT) |

12155 |

3261 |

4443 |

4451 |

5309 |

|||

Cerambycidae and Buprestidae

Within the order Coleoptera, 15 species of Cerambycidae were recorded with PT. An average of 9.7 ± 9 individuals and 5.7 ± 4 species per MAP field were assessed. White and yellow PT collected 55% and 45% of the individuals, respectively. A total of seven species of Buprestidae were collected, resulting in an average of 4 ± 1 species and 29.7 ± 21.1 individuals per MAP field. 90% of Buprestidae were collected with yellow PT and 10% with white PT. When PT B was considered, no differences in species richness for either family were recorded. The abundance of each species and species richness per MAP field is listed in Table 3.

Tab. 3: Abundance and species richness of Cerambycidae and Buprestidae recorded with Malaise traps (MT) in Merano/Meran (M) and with pan traps (PT) in each medicinal and aromatic plant field (M, K = Kastelruth/Castelrotto, W = Wiesen/Prati). For W, values with (+ PT B) and without (- PT B) the additional pan trap set are indicated.

Taxa |

PT |

MT |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Cerambycidae |

Abundance |

M |

K |

W (- PT B) |

W (+ PT B) |

Abundance |

Pseudovadonia livida (Fabricius, 1776) |

3 |

|

|

3 |

3 |

1 |

Xylotrechus smei/stebbingi(Chevrolat, 1860) |

|

|

1 |

|||

Stenurella melanura (Linnaeus, 1758) |

8 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Pachytodes cerambyciformis (Schrank, 1781) |

6 |

1 |

|

|

||

Cerambyx scopoli (Füssli, 1775) |

2 |

1 |

|

|

||

Dinoptera collaris (Linnaeus, 1758) |

7 |

6 |

10 |

|

||

Stenurella nigra (Linnaeus, 1758) |

7 |

1 |

2 |

|

||

Molorchus minor (Linnaeus, 1758) |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

||

Gaurotes virginea (Linnaeus, 1758) |

3 |

2 |

2 |

|

||

Brachyta interrogationis (Linnaeus, 1758) |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

||

Rudpela maculata (Poda, 1761) |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Chlorophorus figuratus (Scopoli, 1763) |

3 |

1 |

|

|

||

Chlorophorus sartor (O. F. Müller, 1766) |

2 |

1 |

|

|

||

Stenopterus ater (Linnaeus, 1767) |

2 |

1 |

|

|

||

Paracorymbiama culicornis (De Geer, 1775) |

3 |

2 |

2 |

|

||

Anastrangalia dubia (Scopoli, 1763) |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

||

Abundance |

57 |

4 |

5 |

20 |

25 |

2 |

Species richness |

15 |

2 |

5 |

10 |

10 |

2 |

Buprestidae |

Abundance |

M |

K |

W (- PT B) |

W (+ PT B) |

|

Anthaxia quadripunctata (Linnaeus, 1758) |

71 |

10 |

42 |

19 |

19 |

|

Acmaeodera bipunctata (Olivier, 1790) |

4 |

1 |

3 |

|

||

Anthaxia podolica (Mannerheim, 1837) |

7 |

1 |

6 |

|

||

Anthaxia nitidula (Linnaeus, 1758) |

2 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

||

Anthaxia helvetica (Stierlin, 1868) |

3 |

3 |

4 |

|||

Agrilus integerrimus (Ratzeburg, 1837) |

1 |

1 |

|

|||

Agrilus viridis (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|||

Abundance |

89 |

12 |

53 |

24 |

28 |

|

Species richness |

7 |

3 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

|

Wild bees

- [31] Nieto A., Roberts S.P.M., Kemp J. et al. (2014). European Red List of bees. Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, Luxembourg, DOI: 10.2779/77003.

- [32] Scheuchl E., Willner W. (2016). Taschenlexikon der Wildbienen. Alle Arten im Porträt. Quelle und Mayer, Wiebelsheim, Germany, here pp. 100-817.

- [33] Westrich P. (2018). Die Wildbienen Deutschlands. Ulmer, Stuttgart, Germany, here pp. 399-719.

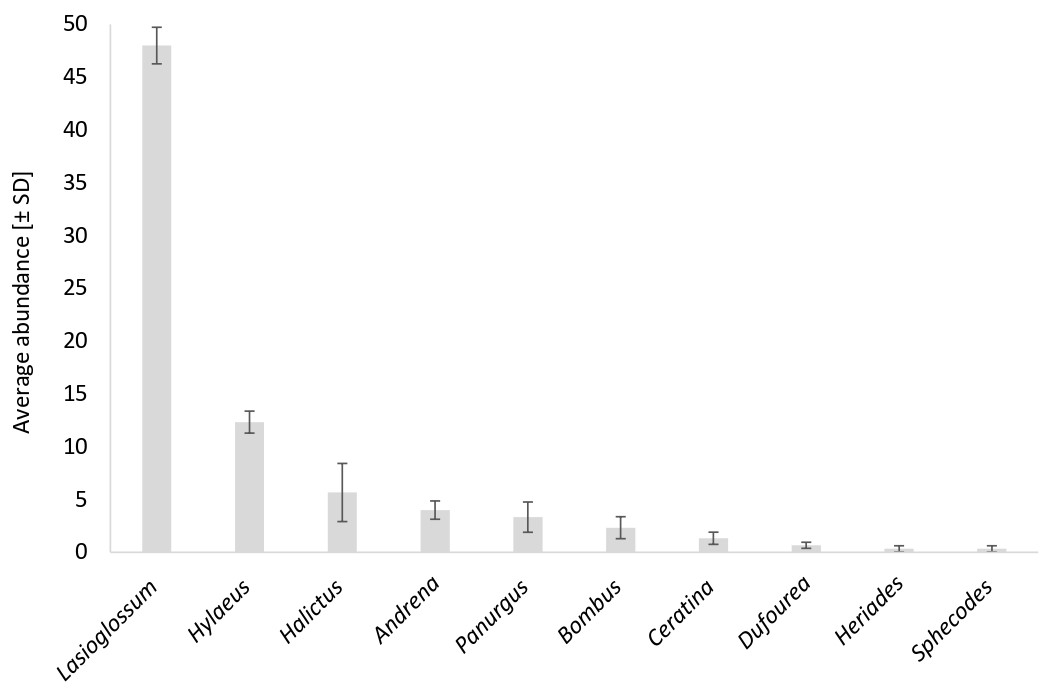

Fig. 3: Average abundance and standard deviation per medicinal and aromatic plant field for each wild bee genus, including individuals identified to genus level.

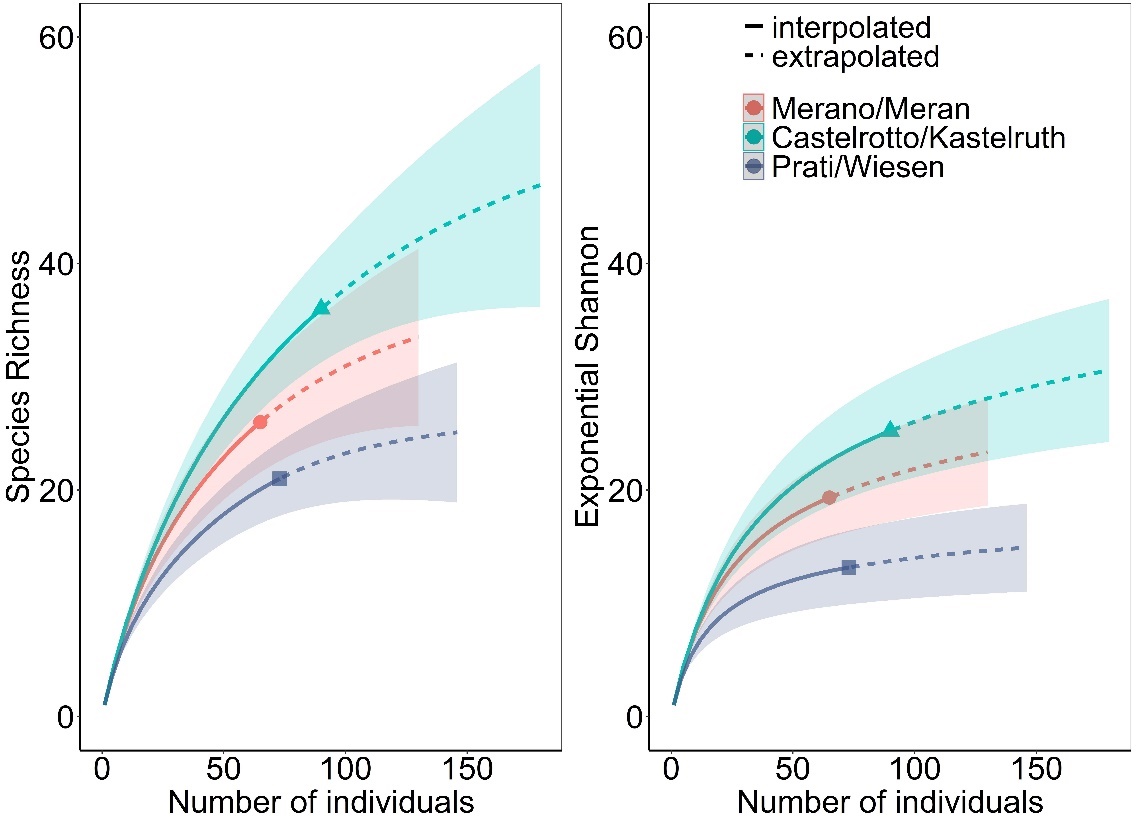

Fig. 4: Accumulation curves of wild bee species richness and wild bee diversity per medicinal and aromatic plant field. A higher wild bee diversity was recorded in Castelrotto/Kastelruth than in Prati/Wiesen, Merano/Meran scored intermediate.

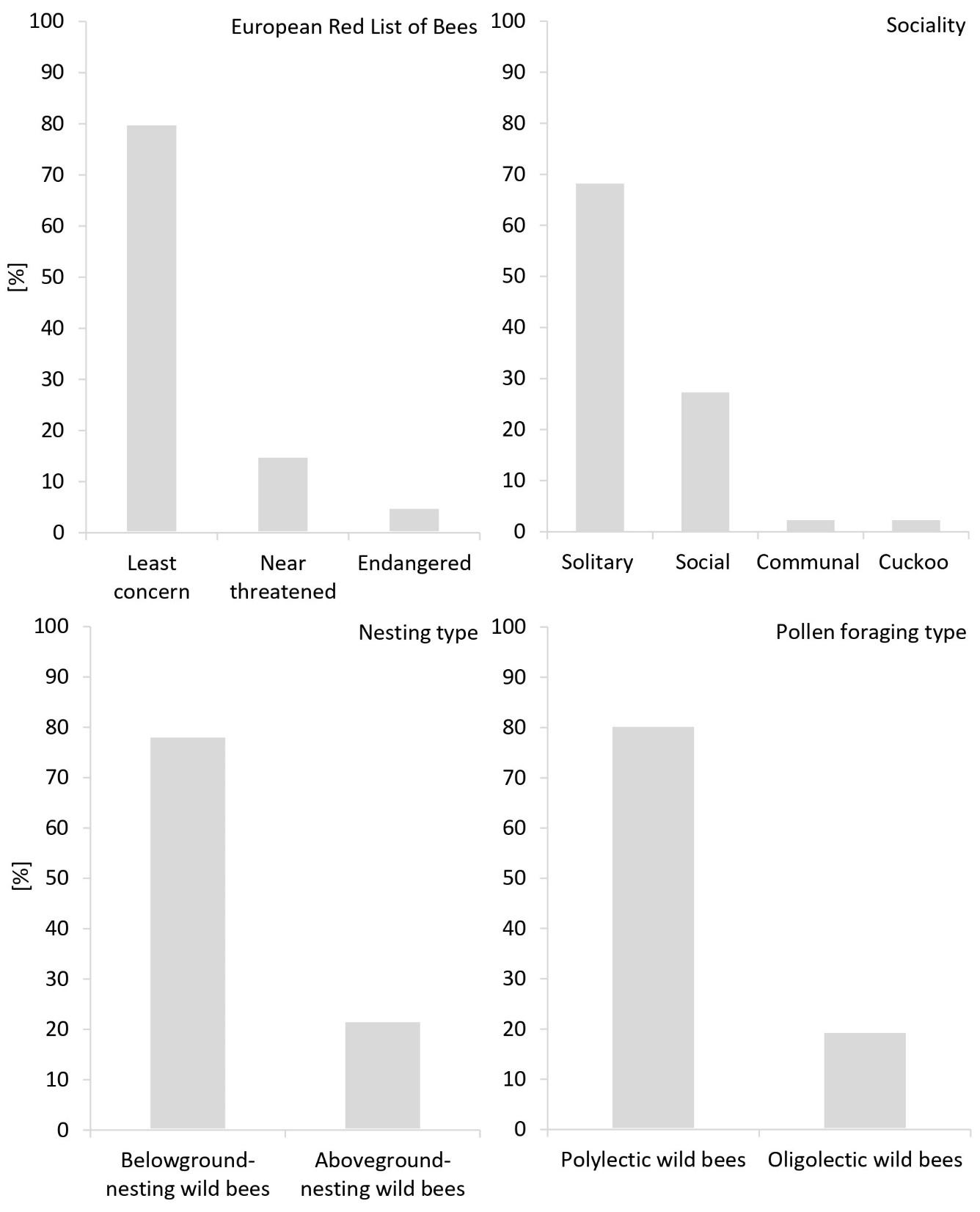

Fig. 5: Percentage of wild bees per European Red List category (46 sp.), sociality (47 sp.), nesting type (46 sp.) and pollen foraging type (46 sp.). For one wild bee speciesh, the European Red List category was not available. Cuckoo bees were excluded from nesting type and pollen foraging type.

Tab. 4: Abundance of wild bees recorded with Malaise traps (MT) in Merano/Meran (M) and with pan traps (PT) in each medicinal and aromatic plant field (MAP) (M, K = Kastelruth/Castelrotto, W = Wiesen/Prati). For W, values with (+ PT B) and without (- PT B) the additional pan trap set are indicated. Average abundance (± SD) per MAP field and species, which were collected with PT, were calculated with M, K, and W (- PT B).

MT |

PT |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Taxa |

Abundance |

Abundance |

M |

K |

W (-PT B) |

W (+ PT B) |

Average (± SD)/MAP field |

Andrena sp. |

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

Andrena fulvago (Christ, 1791) |

2 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

1 (SD ± 1) |

||

Andrena haemorrhoa (Fabricius, 1781) |

|

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

|||

Andrena hattorfiana (Fabricius, 1775) |

|

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

|||

Andrena humilis (Imhoff, 1832) |

|

2 |

2 |

2 |

0.7 (SD ± 1.2) |

||

Andrena minutula (Kirby, 1802) |

|

2 |

1 |

1 |

0.7 (SD ± 0.6) |

||

Andrena nitida (Müller, 1776) |

|

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

|||

Andrena ovatula (Kirby, 1802) |

|

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

|||

Bombus humilis (Illiger, 1806) |

1 |

|

|

||||

Bombus lapidarius (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

2 (SD ± 1.7) |

||

Bombus lucorum (Linnaeus, 1761) |

|

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

|||

Ceratina cucurbitina (Rossi, 1792) |

|

4 |

2 |

2 |

1.3 (SD ± 1.2) |

||

Dufourea dentiventris (Nylander, 1848) |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

||

Dufourea paradoxa (Morawitz, 1868) |

|

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

|||

Halictus eurygnathus (Blüthgen, 1931) |

|

2 |

1 |

1 |

0.7 (SD ± 0.6) |

||

Halictus maculatus (Smith, 1848) |

|

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 (SD ± 1) |

|

Halictus quadricinctus (Fabricius, 1776) |

|

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

|||

Halictus simplex (Blüthgen, 1923) |

|

6 |

6 |

2 (SD ± 3.5) |

|||

Halictus subauratus (Rossi, 1792) |

1 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

1.3 (SD ± 1.2) |

||

Halictus tumulorum (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

||

Heriades crenulatus (Nylander, 1856) |

|

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

|||

Hylaeus annularis (Kirby, 1802) |

|

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

|||

Hylaeus annulatus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

|

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0.7 (SD ± 0.6) |

|

Hylaeus brevicornis (Nylander, 1852) |

|

4 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

1.3 (SD ± 1.2) |

|

Hylaeus communis (Nylander, 1852) |

|

10 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

3.3 (SD ± 1.5) |

Hylaeus confusus (Nylander, 1852) |

|

12 |

4 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

4 (SD ± 2) |

Hylaeus hyalinatus (Smith, 1842) |

|

14 |

6 |

8 |

8 |

4.7 (SD ± 4.2) |

|

Hylaeus nigritus (Fabricius, 1798) |

|

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 (SD ± 0) |

Lasioglossum sp. |

|

6 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

2 (SD ± 1) |

Lasioglossum albipes (Fabricius, 1781) |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0.7 (SD ± 0.6) |

|

Lasioglossum calceatum (Scopoli, 1763) |

2 |

14 |

5 |

2 |

7 |

7 |

4.7 (SD ± 2.5) |

Lasioglossum corvinum (Morawitz, 1877) |

|

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 (SD ± 1) |

||

Lasioglossum griseolum (Morawitz, 1872) |

|

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

|||

Lasioglossum interruptum (Panzer, 1798) |

|

4 |

1 |

3 |

1.3 (SD ± 1.5) |

||

Lasioglossum laeve (Kirby, 1802) |

|

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

|||

Lasioglossum laevigatum (Kirby, 1802) |

1 |

29 |

7 |

3 |

19 |

19 |

9.7 (SD ± 8.3) |

Lasioglossum leucopus (Kirby, 1802) |

|

4 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

Lasioglossum lucidulum (Schenk, 1861) |

|

3 |

3 |

1 (SD ± 1.7) |

|||

Lasioglossum minutulum (Schenk, 1853) |

|

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

|||

Lasioglossum morio (Fabricius, 1793) |

3 |

27 |

9 |

15 |

3 |

4 |

9 (SD ± 6) |

Lasioglossum pauperatum (Brullé, 1832) |

|

2 |

2 |

0.7 (SD ± 1.2) |

|||

Lasioglossum planulum (Pérez, 1903) |

1 |

|

|

||||

Lasioglossum politum (Schenk, 1853) |

|

6 |

6 |

2 (SD ± 3.5) |

|||

Lasioglossum punctatissimum (Schenk, 1853) |

3 |

|

|

||||

Lasioglossum quadrisignatum (Schenk, 1853) |

|

3 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 (SD ± 1) |

|

Lasioglossum semilucens (Alfken, 1914) |

2 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1.7 (SD ± 1.5) |

|

Lasioglossum subhirtum (Lepeletier, 1841) |

|

6 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

2 (SD ± 1) |

Lasioglossum tricinctum (Schenk, 1874) |

|

4 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1.3(SD ± 0.6) |

Lasioglossum zonulum (Smith, 1848) |

|

14 |

7 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4.7 (SD ± 2.1) |

Panurgus banksianus (Kirby, 1802) |

|

8 |

1 |

7 |

8 |

2.7 (SD ± 3.8) |

|

Panurgus calcaratus (Scopoli, 1763) |

|

2 |

2 |

0.7 (SD ± 1.2) |

|||

Sphecodes niger (Hagens, 1874) |

|

1 |

1 |

0.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

|||

Abundance |

20 |

235 |

67 |

91 |

77 |

81 |

|

Species Richness |

12 |

47 |

26 |

36 |

21 |

21 |

|

Tab. 5: Red List category (EN = endangered, NT = near threatened, LC = least concern, DD = data deficient) and functional traits (PFT = pollen foraging type, PFS = plant family specialization, S = Sociality, NT = Nesting type) of wild bees.

Taxa |

Red List [31]

×

|

PFT |

PFS |

S |

NT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Andrena fulvago |

DD |

oligolectic |

Asteraceae |

solitary |

below-ground |

Andrena haemorrhoa |

LC |

polylectic |

solitary |

below-ground |

|

Andrena hattorfiana |

NT |

oligolectic |

Caprifoliaceae |

solitary |

below-ground |

Andrena humilis |

DD |

oligolectic |

Asteraceae |

solitary |

below-ground |

Andrena minutula |

DD |

polylectic |

solitary |

below-ground |

|

Andrena nitida |

LC |

polylectic |

solitary |

below-ground |

|

Andrena ovatula |

NT |

polylectic |

solitary |

below-ground |

|

Bombus humilis |

LC |

polylectic |

eusocial |

above-ground |

|

Bombus lapidarius |

LC |

polylectic |

eusocial |

above-ground |

|

Bombus lucorum |

LC |

polylectic |

eusocial |

below-ground |

|

Ceratina cucurbitina |

LC |

polylectic |

solitary |

above-ground |

|

Dufourea dentiventris |

NT |

oligolectic |

Campanulaceae |

solitary |

below-ground |

Dufourea paradoxa |

LC |

polylectic |

solitary |

below-ground |

|

Halictus eurygnathus |

|

polylectic |

solitary |

below-ground |

|

Halictus maculatus |

LC |

polylectic |

eusocial |

below-ground |

|

Halictus quadricinctus |

NT |

polylectic |

solitary |

below-ground |

|

Halictus simplex |

LC |

polylectic |

solitary |

below-ground |

|

Halictus subauratus |

LC |

polylectic |

eusocial |

below-ground |

|

Halictus tumulorum |

LC |

polylectic |

eusocial |

below-ground |

|

Heriades crenulatus |

LC |

oligolectic |

Asteraceae |

solitary |

above-ground |

Hylaeus annularis |

DD |

oligolectic |

Asteraceae |

solitary |

above-ground |

Hylaeus annulatus |

DD |

polylectic |

solitary |

above-ground |

|

Hylaeus brevicornis |

LC |

polylectic |

solitary |

above-ground |

|

Hylaeus communis |

LC |

polylectic |

solitary |

above-ground |

|

Hylaeus confusus |

LC |

polylectic |

solitary |

above-ground |

|

Hylaeus hyalinatus |

LC |

polylectic |

solitary |

above-ground |

|

Hylaeus nigritus |

LC |

oligolectic |

Asteraceae |

solitary |

above-ground |

Lasioglossum albipes |

LC |

polylectic |

eusocial |

below-ground |

|

Lasioglossum calceatum |

LC |

polylectic |

eusocial |

below-ground |

|

Lasioglossum corvinum |

LC |

polylectic |

below-ground |

||

Lasioglossum griseolum |

LC |

polylectic |

below-ground |

||

Lasioglossum interruptum |

LC |

polylectic |

eusocial |

below-ground |

|

Lasioglossum laeve |

EN |

polylectic |

solitary |

below-ground |

|

Lasioglossum laevigatum |

NT |

polylectic |

solitary |

below-ground |

|

Lasioglossum leucopus |

LC |

polylectic |

solitary |

below-ground |

|

Lasioglossum lucidulum |

LC |

polylectic |

solitary |

below-ground |

|

Lasioglossum minutulum |

NT |

polylectic |

solitary |

below-ground |

|

Lasioglossum morio |

LC |

polylectic |

eusocial |

below-ground |

|

Lasioglossum pauperatum |

LC |

polylectic |

below-ground |

||

Lasioglossum planulum |

|

polylectic |

below-ground |

||

Lasioglossum politum |

LC |

polylectic |

eusocial |

below-ground |

|

Lasioglossum punctatissimum |

LC |

polylectic |

below-ground |

||

Lasioglossum quadrisignatum |

EN |

polylectic |

below-ground |

||

Lasioglossum semilucens |

LC |

polylectic |

solitary |

below-ground |

|

Lasioglossum subhirtum |

LC |

polylectic |

below-ground |

||

Lasioglossum tricinctum |

DD |

polylectic |

eusocial |

below-ground |

|

Lasioglossum zonulum |

LC |

polylectic |

solitary |

below-ground |

|

Panurgus banksianus |

LC |

oligolectic |

Asteraceae |

solitary |

below-ground |

Panurgus calcaratus |

LC |

oligolectic |

Asteraceae |

communal |

below-ground |

Sphecodes niger |

LC |

|

|

cuckoo bee of Lasioglossum morio |

|

Flowering MAPs and pollinators

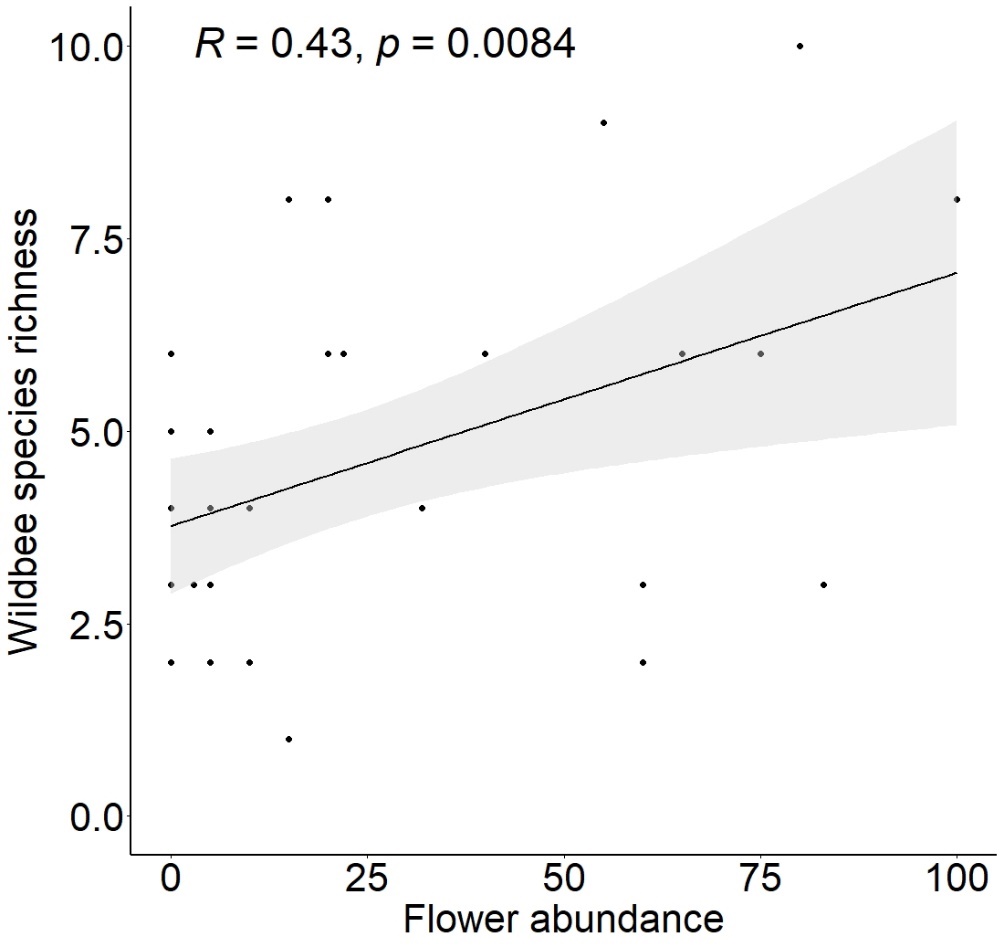

Abundance of Syrphidae, A. mellifera and wildbees did not correlate significantly with MAP flower abundance. However, a positive correlation was detected for wild bee species richness (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Significant effect of flower abundance on wild bee species richness. Flower abundance was calculated as the percentage of medicinal and aromatic plants in flower (0-100) around each pan trap set. Dots represent raw data per survey event and bands represent the 95% confidence interval.

Hymenopteran parasitoids

- [22] Goulet H., Huber J.T. (eds.) (1993). Hymenoptera of the world. An identification guide to families. Canada Communication Group, Ottawa, Canada, here pp. 65-529.

Tab. 6: Abundance and family richness of Hymenopteran parasitoids recorded with Malaise traps in Merano/Meran (M) and with pan traps in each medicinal and aromatic plant field (MAP) (M, K = Kastelruth/Castelrotto, W = Wiesen/Prati). For W, values with (+ PT B) and without (- PT B) the additional pan trap set are indicated. Average abundance (± SD) per MAP field and taxon were calculated with M, K, and W (- PT B).

MT |

PT |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Taxa |

Abundance |

Abundance |

M |

K |

W (-PT B) |

W (+ PT B) |

Average (± SD)/MAP field |

Braconidae varia |

68 |

30 |

7 |

14 |

9 |

9 |

10 (SD ± 3.6) |

Aphidiinae (Braconidae) |

31 |

11 |

1 |

9 |

1 |

1 |

3.7 (SD ± 4.6) |

Ichneumonidae |

33 |

10 |

6 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

3.3 (SD ± 2.5) |

Cynipoidea varia |

64 |

19 |

4 |

5 |

10 |

12 |

6.3 (SD ± 3.2) |

Chalcidoidea varia (mostly Pteromalidae/Tetracampidae) |

23 |

13 |

3 |

3 |

7 |

7 |

4.3 (SD ± 2.3) |

Aphelinidae |

20 |

9 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

3 (SD ± 1) |

Chalcididae |

1 |

|

|

||||

Elasmidae |

1 |

|

|

||||

Encyrtidae |

29 |

101 |

53 |

48 |

1 |

50.5 (SD ± 3.5) |

|

Eulophidae |

16 |

16 |

6 |

5 |

5 |

7 |

5.3 (SD ± 0.6) |

Eurytomidae |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|||

Mymaridae |

120 |

21 |

4 |

11 |

6 |

10 |

7 (SD ± 3.6) |

Signiphoridae |

2 |

|

|

||||

Trichogrammatidae |

4 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 (SD ± 0) |

|

Torymidae |

1 |

|

|

||||

Ceraphronidae |

7 |

19 |

3 |

3 |

13 |

14 |

6.3 (SD ± 5.8) |

Megaspilidae |

2 |

|

|

||||

Proctotrupidae |

10 |

|

|

||||

Diapriidae |

24 |

13 |

3 |

9 |

1 |

1 |

4.3 (SD ± 4.2) |

Evaniidae |

2 |

|

|

||||

Platygastridae |

19 |

11 |

2 |

5 |

4 |

6 |

3.7 (SD ± 1.5) |

Scelionidae |

26 |

52 |

27 |

16 |

9 |

13 |

17.3 (SD ± 9.1) |

Chrysididae |

3 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2.5 (SD ± 0.7) |

|

Dryinidae |

3 |

|

|

||||

Bethylidae |

3 |

|

|

||||

Abundance |

514 |

334 |

123 |

138 |

73 |

90 |

|

Family richness (superfamilies excluded) |

22 |

13 |

9 |

12 |

10 |

11 |

|

Additional surveys

Malaise traps

- [34] Hellrigl K. (2003). Faunistik der Ameisen und Wildbienen Südtirols (Hymenoptera: Formicidae et Apoidea). Gredleriana 3, 143-208.

Grasshoppers, butterflies, birds, and bats

- [35] Huemer P. (2004). Die Tagfalter Südtirols (Veröffentlichungen des Naturmuseums Suedtirol , 2). Folio Verlag, Vienna, Austria.

- [36] Ceresa F., Kranebitter P. (2020). Lista Rossa 2020 degli uccelli nidificanti in Alto Adige. Gredleriana 20, 57-70.

- [37] Hilpold A., Wilhalm T., Kranebitter P. (2017). Rote Liste der gefährdeten Fang- und Heuschrecken Südtirols (Insecta: Orthoptera, Mantodea). Gredleriana 17, 61-86.

- [38] Rondinini C., Battistoni A., Teofili C. (2022). Lista Rossa IUCN dei Vertebrati Italiani 2022. Comitato Italiano IUCN e Ministero dell'Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare, Roma, Italia, here p. 31.

- [39] Dietz C., Kiefer A. (2016). Bats of Britain and Europe. Bloomsbury Publishing, London, United Kingdom, here pp. 104-105.

Tab. 7: Abundance and Red List category (LC = least concern, NE = not evaluated, NT = near threatened) of grasshopper and butterfly species recorded in M (Merano/Meran).

Grasshoppers |

Abundance |

|

Chorthippus brunneus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

4 |

LC |

Mantis religiosa (Linnaeus, 1758) |

2 |

LC |

Gomphocerippus rufus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

LC |

Gryllus campestris (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

LC |

Oedipoda caerulescens (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

LC |

Butterflies |

Abundance |

|

Pieris rapae (Linnaeus, 1758) |

79 |

LC |

Polyommatus icarus (Rottemburg, 1775) |

23 |

LC |

Pieris napi (Linnaeus, 1758) |

6 |

LC |

Vanessa cardui (Linnaeus, 1758) |

3 |

NE |

Colias croceus (Geoffrey in Fourcroy, 1785) |

2 |

NE |

Vanessa atalanta (Linnaeus, 1758) |

2 |

NE |

Lysandra bellargus (Rottemburg, 1775) |

1 |

LC |

Pieris brassicae (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

NT |

Tab. 8: Abundance and Red List category (EN = endangered, VU = vulnerable, NT = near threatened, LC = least concern, DD = data deficient, NE = not evaluated) of birds and bats in medicinal and aromatic plant fields. For birds, abundance in M (Meran/Merano) and W (Wiesen/Prati) are listed separately. For bats recorded in M, the total calls and the number of feeding buzzes are listed.

Birds |

Abundance M |

Abundance W |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Passer italiae (Vieillot, 1817) |

|

10 |

VU |

Turdus merula (Linnaeus, 1758) |

7 |

3 |

LC |

Sylvia atricapilla (Linnaeus, 1758) |

5 |

4 |

LC |

Passer montanus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

5 |

1 |

EN |

Hirundo rustica (Linnaeus, 1758) |

5 |

LC |

|

Carduelis carduelis (Linnaeus, 1758) |

4 |

|

LC |

Corvus corone (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

2 |

LC |

Fringilla coelebs (Linnaeus, 1758) |

3 |

|

LC |

Serinus serinus (Linnaeus, 1766) |

2 |

1 |

LC |

Chloris chloris (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

1 |

EN |

Parus major (Linnaeus, 1758) |

2 |

LC |

|

Phoenicurus ochruros (S. G. Gmelin, 1774) |

2 |

LC |

|

Pica pica (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

1 |

LC |

Turdus pilaris (Linnaeus, 1758) |

2 |

|

NT |

Aquila chrysaetos (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

VU |

|

Columba palumbus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

|

LC |

Dendrocopos major (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

|

LC |

Erithacus rubecula (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

LC |

|

Jynx torquilla (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

|

DD |

Phoenicurus phoenicurus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

VU |

|

Turdus philomelos (C. L. Brehm, 1831) |

1 |

|

LC |

Turdus viscivorus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

|

LC |

Bats |

Total calls |

Feeding buzzes |

|

Rhinolophus hipposideros (Borkhausen, 1797) |

38 |

1 |

EN |

Pipistrellus pipistrellus (Schreber, 1774) |

27 |

6 |

LC |

Nyctalus/Vespertilio/Eptesicus |

17 |

1 |

|

Pipistrellus kuhlii/nathusii |

10 |

4 |

LC/NT |

Myotis myotis/Myotis blythii |

9 |

|

VU |

Pipistrellus pygmaeus (Leach, 1825) |

9 |

2 |

NT |

Myotis sp. |

7 |

|

|

Hypsugo savii (Bonaparte, 1837) |

2 |

1 |

LC |

Nyctalus leisleri (Kuhl, 1817) |

1 |

|

NT |

Pipistrellus sp. |

1 |

|

|

Plecotus macrobullaris/auritus |

1 |

|

EN/NT |

Ground-dwelling macro-invertebrates

- [40] Origazzi A., Bardgett R., Barrios E. et al. (2016). Global Soil Biodiversity Atlas. Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, Luxembourg, here pp. 28-65.

- [41] Bellmann H. (20063). Kosmos-Atlas Spinnentiere Europas. Kosmos, Stuttgart, Germany, here pp. 20-254.

- [42] Koch K. (1999). Carabidae - Micropeplidae. In: Die Käfer Mitteleuropas (Bd. E1). Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany.

- [43] Schöller M. (1996). Ökologie mitteleuropäischer Blattkäfer, Samenkäfer und Breitrüssler. Eigenverlag des EVCV, Bürs, Austria, here pp. 5-11.

- [44] Rheinheimer J., Hassler M. (2013). Rüsselkäfer Baden-Württembergs. Verlag Regionalkultur, Heidelberg, Germany, here pp. 31-67.

- [45] Klausnitzer B. (2011). Stresemann - Exkursionsfauna von Deutschland. Bd. 2: Wirbellose. Insekten. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany, here pp. 111-316.

- [46] Harde K.W., Helb M., Elzner K. (2021). Der Kosmos Käferführer. Franckh-Kosmos Verlag, Stuttgart, Germany, here pp. 96-259.

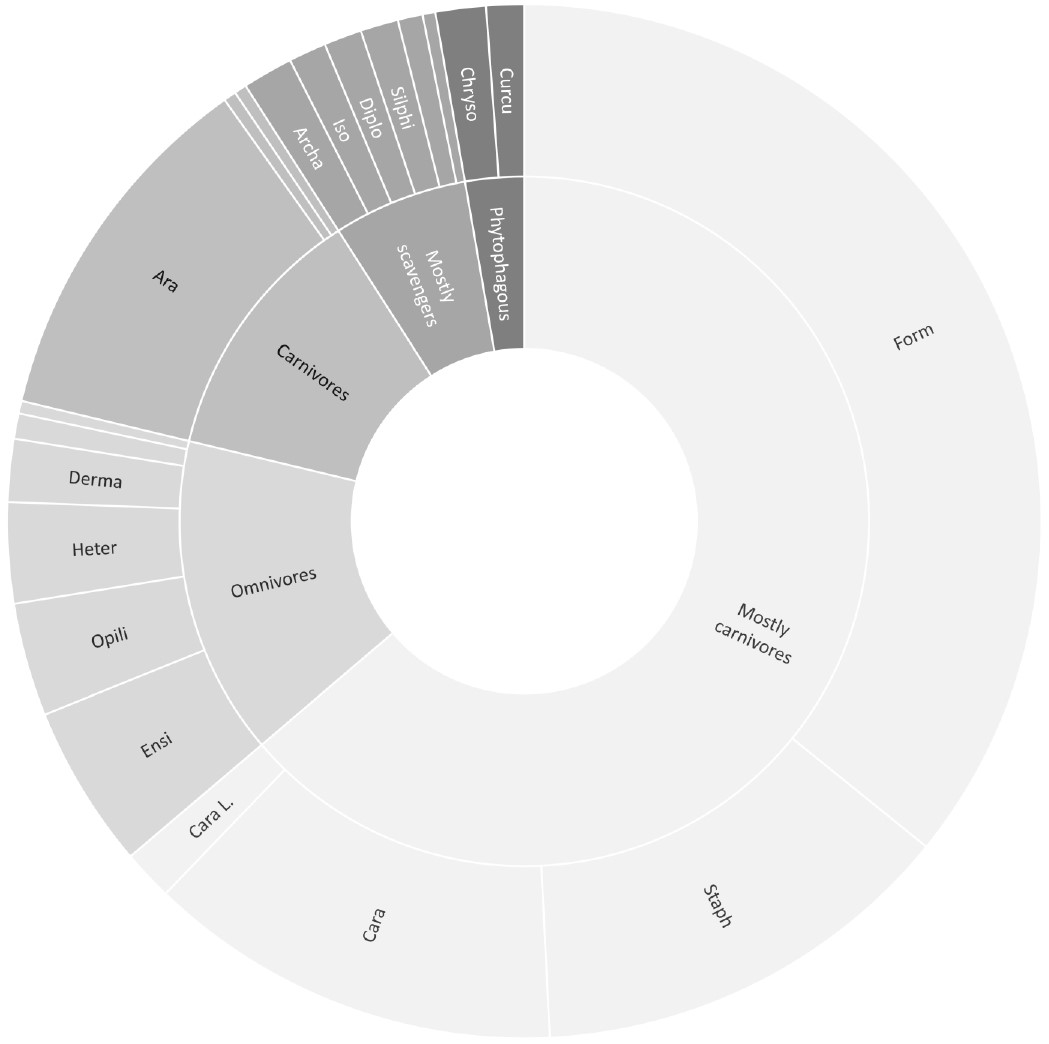

Fig. 7: Percentage of taxa collected with pitfall traps, subdivided according to their trophic guild. Only target taxa of pitfall traps were included (Form = Formicidae, Staph = Staphilinidae, Cara = Carabidae, Cara L. = Carabidae Larvae Ensi = Ensifera, Opili = Opiliones, Heter = Heteroptera, Derma = Dermaptera, Ara = Araneae, Archa = Archaeognatha, Iso = Isopoda, Diplo = Diplopoda, Silphi = Silphidae, Chryso = Chrysomelidae, Curcu = Curculionidae).

Tab. 9: Abundance of ground-dwelling macro-invertebrates collected with pitfall traps in Merano/Meran. Ground-dwelling macro-invertebrates are divided into non-target and target taxa. For the latter, the trophic guild and corresponding reference are listed.

Taxa |

Abundance |

Trophic guild |

Reference |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Target taxa |

Isopoda |

3 |

Scavengers (mostly) |

|

Araneae |

29 |

Carnivors |

||

Pseudoscorpiones |

1 |

Carnivors |

||

Opiliones |

9 |

Omnivores |

||

Chilopoda_Lithobiidae |

1 |

Carnivors |

||

Diplopoda_Julidae |

3 |

Scavengers (mostly) |

||

Carabidae |

33 |

Carnivors (mostly) |

||

Chrysomelidae |

4 |

Phytophagous |

||

Curculionidae |

3 |

Phytophagous |

||

Elateridae |

1 |

Omnivores |

||

Scarabaeidae |

2 |

Omnivores |

||

Silphidae |

3 |

Scavengers (mostly) |

||

Staphylinidae |

34 |

Carnivors (mostly) |

||

Carabidae Larvae |

4 |

Carnivors (mostly) |

||

Silphidae Larvae |

2 |

Scavengers (mostly) |

||

Dermestidae Larvae |

1 |

Scavengers (mostly) |

||

Formicidae |

91 |

Carnivors (mostly) |

||

Heteroptera |

8 |

Omnivores |

||

Dermaptera |

5 |

Omnivores |

||

Ensifera |

13 |

Omnivores |

||

Archaeognatha |

4 |

Scavengers (mostly) |

||

Non-target taxa |

Lumbricidae |

2 |

||

Brachycera/Nematocera |

65 |

|||

Hymenoptera |

8 |

|||

Sternorrhyncha |

1 |

|||

Auchenorrhyncha |

21 |

|||

Lepidoptera Larvae |

1 |

Discussion

- [10] Licata M., Maggio A.M., La Bella S. et al. (2022). Medicinal and aromatic plants in agricultural research, when considering criteria of multifunctionality and sustainability. Agriculture 12 (4), 529, DOI: 10.3390/agriculture12040529.

- [47] Wilson J.D., Whittingham M.J., Bradbury R.D. (2005). The management of crop structure. A general approach to reversing the impacts of agricultural intensification on birds? Ibis 147 (3), 453-463, DOI: 10.1111/j.1474-919x.2005.00440.x.

- [48] O’Neill K.M., Fultz J.E., Ivie M.A. (2008). Distribution of adult Cerambycidae and Buprestidae (Coleoptera) in a subalpine forest under shelterwood management. The Coleopterists Bulletin, 62 (1), 27-36.

- [49] Sakalian V., Langourov M. (2004). Colour traps a method for distributional and ecological investigations of Buprestidae (Coleoptera). Acta Societatis Zoologicae Bohemicae 68, 53-59.

- [50] Klausnitzer B., Klausnitzer U., Wachmann E. et al. (2016). Die Bockkäfer Mitteleuropas. VerlagsKG Wolf, Magdeburg, Germany, here pp. 118-133.

- [51] Földesi R., Kovács-Hostyánszki A., Korösi A. et al. (2016). Relationships between wild bees, hoverflies and pollination success in apple orchards with different landscape contexts. Agricultural and Forest Entomology 18 (1), 68-75, DOI: 10.1111/afe.12135.

- [52] Roquer-Beni L., Alins G., Arnan X., et al. (2021). Management-dependent effects of pollinator functional diversity on apple pollination services: A response-effect trait approach. Journal of Applied Ecology 58 (12), 2843-2853, DOI: 10.1111/1365-2664.14022.

- [17] Venkatesh Y.N., Neethu T., Ashajyothi M. et al. (2022). Pollinator activity and their role on seed set of medicinal and aromatic Lamiaceae plants. Journal of Apicultural Research, Vol. ahead-of-print, DOI: 10.1080/00218839.2022.2080949.

- [53] Ahrné K., Bengtsson J., Elmqvist T. (2009). Bumble Bees (Bombus spp) along a gradient of increasing urbanization. PLoS One 4:e5574, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005574.

- [54] Kuppler J., Neumüller U, Mayr A.V. et al. (2023). Favourite plants of wild bees. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 342:108266, DOI: 10.1016/j.agee.2022.108266.

- [55] Schindler M., Diestelhorst O., Härtel S. et al. (2013). Monitoring agricultural ecosystems by using wild bees as environmental indicators. BioRisk 8, 53-71, DOI: 10.3897/biorisk.8.3600.

- [14] Meyer U., Blum H., Gärber U. et al. (2010). Praxisleitfaden Krankheiten und Schädlinge im Arznei- und Gewürzpflanzenanbau. Julius-Kühn-Institut Selbstverlag, Braunschweig, Germany.

- [56] Höring T.F. (2014). How aphids find their host plants, and how they don’t. Annals of Applied Biology 165 (1), 3-26, DOI: 10.1111/aab.12142.

- [57] Singh R., Singh G. (2016). Aphids and their biocontrol. In: Omkar (ed.). Ecofriendly Pest Management for Food Security. Academic Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, here pp. 63-108.

- [58] Haddad N.M., Crutsinger G.M., Gross K. et al. (2010). Plant diversity and the stability of food webs. Ecology Letters 14 (1), 42-46, DOI: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01548.x.

- [59] Wan N.-F., Zheng X.-R., Fu L.-W. et al. (2020). Global synthesis of effects of plant species diversity on trophic groups and interactions. Nature Plants 6 (5), 503-510, DOI: 10.1038/s41477-020-0654-y.

- [60] Dassou A.G., Tixier P. (2016). Response of pest control by generalist predators to local-scale plant diversity. A meta-analysis. Ecology and Evolution 6 (4), 1143-1153, DOI: 10.1002/ece3.1917.

- [24] Anderle M., Paniccia C., Brambilla M. et al. (2022). The contribution of landscape features, climate and topography in shaping taxonomical and functional diversity of avian communities in a heterogeneous Alpine region. Oecologia, 199, 499-512, DOI: 10.1007/s00442-022-05134-7.

- [61] Martin E.A., Dainese M., Clough Y., et al. (2019). The interplay of landscape composition and configuration. New pathways to manage functional biodiversity and agroecosystem services across Europe. Ecology Letters, 22 (7), 1083-1094, DOI: 10.1111/ele.13265.

- [35] Huemer P. (2004). Die Tagfalter Südtirols (Veröffentlichungen des Naturmuseums Suedtirol , 2). Folio Verlag, Vienna, Austria.

- [62] Tscharntke T., Grass I., Wanger T.C. et al. (2021). Beyond organic farming. Harnessing biodiversity-friendly landscapes. Trend in Ecology and Evolution 36 (10), 919-930, DOI: 10.1016/j.tree.2021.06.010.

- [63] Cramp S., Simmons A.D., Perrins C.M. (1994). Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. The Birds of the Western Palaearctic. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, here pp. 54, 288.

Overall, there is great potential for further research addressing biodiversity in MAP fields from multiple perspectives. Although the sampling effort was not equal for all MAP fields and taxa, our results show that the studied MAP fields functioned as a resource-rich oases for a variety of taxa, ranging from lower trophic levels such as herbivores and pollinators to birds and bats. We conclude that small-scale MAP cultivation may aid the conservation of various taxa and the promotion of biodiversity in a landscape dominated by agriculture.

Acknowledgements

This research was co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund through the Interreg Alpine Space Programme (LUIGI: Linking Urban and Inner-alpine Green Infrastructure, project number ASP 863). Furthermore, we thank all farmers for granting us access to the survey sites and Luciano Filippi (Cecina, Italy) for his great contribution in the identification of wild bees.

References

- [1] Máthé Á. (2015). Utilization/Significance of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. In: Máthé Á (ed.). Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of the World. Scientific, Production, Commercial and Utilization Aspects. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany, here pp. 1-12, DOI: 10.1007/978-94-017-9810-5.

- [2] Ahad B., Shahri W., Rasool H. et al. (2021). Medicinal Plants and Herbal Drugs. An Overview. In: Aftab T., Hakeem K.R. (eds.). Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Healthcare and Industrial Applications. Springer, Cham, Switzerland, here p. 2, DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-58975-2_1.

- [3] Lubbe A., Verpoorte R. (2011). Cultivation of medicinal and aromatic plants for specialty industrial materials. Industrial Crops and Products 34 (1), 785-801, DOI: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2011.01.019.

- [4] Leaman D.J. (2008). Conservation and Sustainable Use of Wild-sourced Botanicals. Planta Medica, 74, 11, DOI: 10.1055/s-2008-1075152.

- [5] Shippmann U., Leaman D.J., Cunningham A.B. (2002). Impact of Cultivation and Gathering of Medicinal Plants on Biodiversity. Global Trends and Issues. In: Biodiversity and the Ecosystem Approach in Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Satellite event on the occasion of the Ninth Regular Session of the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, Rome, Italy, October 12-13, 2002. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

- [6] Salomon I., Haban M., Otepka P. et al. (2018). Perspectives of small- and large- scale cultivation of medicinal, aromatic and spice plants in Slovakia. Medicinal Plants 10 (4), 261-267, DOI: 10.5958/0975-6892.2018.00041.2.

- [7] Allen D., Bilz M., Leaman D.J. et al. (2014). European Red List of Medicinal Plants. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, Luxembourg, here p. 4.

- [8] Südtiroler Bauernbund (ed.) (2014). Nischenkulturen als Erwerbsmöglichkeit. Chance und Herausforderung für die Südtiroler Landwirtschaft. Südtiroler Bauernbund, Bozen/Bolzano, Italy. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://issuu.com/effektgmbh/docs/sbb_broschu__re_nischenkulturen.

- [9] Šálek M., Hula V., Kipson M. et al. (2018). Bringing diversity back to agriculture. Smaller fields and non-crop elements enhance biodiversity in intensively managed arable farmlands. Ecological Indicators 90, 65-73, DOI: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.03.001.

- [10] Licata M., Maggio A.M., La Bella S. et al. (2022). Medicinal and aromatic plants in agricultural research, when considering criteria of multifunctionality and sustainability. Agriculture 12 (4), 529, DOI: 10.3390/agriculture12040529.

- [11] Hoppe B. (ed.) (2007). Handbuch des Arznei- und Gewürzpflanzenanbaus. Bd. 3: Krankheiten und Schädigungen an Arznei- und Gewürzpflanzen. SALUPLANTA e. V., Bernburg, Germany.

- [12] Pramsohler M., Gallmetzer A., Castellan A. et al. (2022). Erster Nachweis und molekularbiologische Bestimmung von Donus intermedius (Coleoptera: Curculionoidae) als Schädling bei Zitronenmelisse in Südtirol. Laimburg Journal 4, DOI: 10.23796/LJ/2022.003.

- [13] Nickel H., Blum H., Jung K. (2014). Verbreitung und Biologie der an mitteleuropäischen Arznei- und Gewürzpflanzen schädlichen Blattzikaden (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae, Typhlocybinae). Cicadina 14, 13-42, DOI: 10.25673/92235.

- [14] Meyer U., Blum H., Gärber U. et al. (2010). Praxisleitfaden Krankheiten und Schädlinge im Arznei- und Gewürzpflanzenanbau. Julius-Kühn-Institut Selbstverlag, Braunschweig, Germany.

- [15] Pobożniak M., Sobolewska A. (2011). Biodiversity of thrips species (Thysanoptera) on flowering herbs in Cracow, Poland. Journal of Plant Protection Research 51 (4), 393-398, DOI: 10.2478/v10045-011-0064-2.

- [16] Gupta S.K., Karmakar K. (2011). Diversity of mites (Acari) on medicinal and aromatic plants in India. Zoosymposia 6, 56-61, DOI: 10.11646/zoosymposia.6.1.10.

- [17] Venkatesh Y.N., Neethu T., Ashajyothi M. et al. (2022). Pollinator activity and their role on seed set of medicinal and aromatic Lamiaceae plants. Journal of Apicultural Research, Vol. ahead-of-print, DOI: 10.1080/00218839.2022.2080949.

- [18] Kumari B., Ravinder R. (2017). Pollination studies in Tagetes minuta, an important medicinal and aromatic plant. Medicinal Plants – International Journal of Phytomedicines and Related Industries 9 (2), 140-142, DOI: 10.5958/0975-6892.2017.00021.1.

- [19] Hilpold A., Anderle M., Guariento E. et al. (2023). Handbook - Biodiversity Monitoring South Tyrol. Eurac Research, Bolzano, Italy, DOI: 10.57749/2qm9-fq40.

- [20] Vrdoljak S.M., Samways M.J. (2010). Optimising coloured pan traps to survey flower visiting insects. Journal of Insect Conservation 16, 345-354, DOI: 10.1007/s10841-011-9420-9.

- [21] Droege S., Tepedino V.J., Lebuhn G. et al. (2010). Spatial patterns of bee captures in North American bowl trapping surveys. Insect Conservation and Diversity 3 (1), 15-23, DOI: 10.1111/j.1752-4598.2009.00074.x.

- [22] Goulet H., Huber J.T. (eds.) (1993). Hymenoptera of the world. An identification guide to families. Canada Communication Group, Ottawa, Canada, here pp. 65-529.

- [23] Bibby C.J., Burgess N.D., Hillis D.M. et al. (2000). Bird census techniques. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom, here pp. 91-112.

- [24] Anderle M., Paniccia C., Brambilla M. et al. (2022). The contribution of landscape features, climate and topography in shaping taxonomical and functional diversity of avian communities in a heterogeneous Alpine region. Oecologia, 199, 499-512, DOI: 10.1007/s00442-022-05134-7.

- [25] Fornasari L., Mingozzi T. (1999). Monitoraggio dell'avifauna nidificante in Italia. Un progetto pluriennale sulle specie comuni. Avocetta - Journal of Ornithology, 23, 153-153.

- [26] Barataud M. (2015). Acoustic ecology of European bats. Species Identification and Studies of Their Habitats and Foraging Behaviour. Biotope & National Museum of Natural History, Paris, France, here pp. 104-263.

- [27] Teets K.D., Loeb S.C., Jachowski D.S. (2019). Detection probability of bats using active versus passive monitoring. Acta Chiropterologica 21 (1), 205-213, DOI: 10.3161/15081109ACC2019.21.1.017.

- [28] Hilpold A., Kirschner P., Dengler J. (2020). Proposal of a standardized EDGG surveying methodology for orthopteroid insects. Palaearctic Grasslands 46, 52-57, DOI: 10.21570/EDGG.PG.46.52-57.

- [29] Guariento E., Rüdisser J., Fiedler K. et al. (2022). From diverse to simple: butterfly communities erode from extensive grasslands to intensively used farmland and urban areas. Biodiversity and Conservation 32, 867-882, DOI: 10.1007/s10531-022-02498-3.

- [30] Hsieh T.C., Ma K.H., Chao A. (2016). iNEXT: an R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers). Methods of Ecology and Evolution 7 (12), 1451-1456, DOI: 10.1111/2041-210X.12613.

- [31] Nieto A., Roberts S.P.M., Kemp J. et al. (2014). European Red List of bees. Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, Luxembourg, DOI: 10.2779/77003.

- [32] Scheuchl E., Willner W. (2016). Taschenlexikon der Wildbienen. Alle Arten im Porträt. Quelle und Mayer, Wiebelsheim, Germany, here pp. 100-817.

- [33] Westrich P. (2018). Die Wildbienen Deutschlands. Ulmer, Stuttgart, Germany, here pp. 399-719.

- [34] Hellrigl K. (2003). Faunistik der Ameisen und Wildbienen Südtirols (Hymenoptera: Formicidae et Apoidea). Gredleriana 3, 143-208.

- [35] Huemer P. (2004). Die Tagfalter Südtirols (Veröffentlichungen des Naturmuseums Suedtirol , 2). Folio Verlag, Vienna, Austria.

- [36] Ceresa F., Kranebitter P. (2020). Lista Rossa 2020 degli uccelli nidificanti in Alto Adige. Gredleriana 20, 57-70.

- [37] Hilpold A., Wilhalm T., Kranebitter P. (2017). Rote Liste der gefährdeten Fang- und Heuschrecken Südtirols (Insecta: Orthoptera, Mantodea). Gredleriana 17, 61-86.

- [38] Rondinini C., Battistoni A., Teofili C. (2022). Lista Rossa IUCN dei Vertebrati Italiani 2022. Comitato Italiano IUCN e Ministero dell'Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare, Roma, Italia, here p. 31.

- [39] Dietz C., Kiefer A. (2016). Bats of Britain and Europe. Bloomsbury Publishing, London, United Kingdom, here pp. 104-105.

- [40] Origazzi A., Bardgett R., Barrios E. et al. (2016). Global Soil Biodiversity Atlas. Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, Luxembourg, here pp. 28-65.

- [41] Bellmann H. (20063). Kosmos-Atlas Spinnentiere Europas. Kosmos, Stuttgart, Germany, here pp. 20-254.

- [42] Koch K. (1999). Carabidae - Micropeplidae. In: Die Käfer Mitteleuropas (Bd. E1). Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany.

- [43] Schöller M. (1996). Ökologie mitteleuropäischer Blattkäfer, Samenkäfer und Breitrüssler. Eigenverlag des EVCV, Bürs, Austria, here pp. 5-11.

- [44] Rheinheimer J., Hassler M. (2013). Rüsselkäfer Baden-Württembergs. Verlag Regionalkultur, Heidelberg, Germany, here pp. 31-67.

- [45] Klausnitzer B. (2011). Stresemann - Exkursionsfauna von Deutschland. Bd. 2: Wirbellose. Insekten. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany, here pp. 111-316.

- [46] Harde K.W., Helb M., Elzner K. (2021). Der Kosmos Käferführer. Franckh-Kosmos Verlag, Stuttgart, Germany, here pp. 96-259.

- [47] Wilson J.D., Whittingham M.J., Bradbury R.D. (2005). The management of crop structure. A general approach to reversing the impacts of agricultural intensification on birds? Ibis 147 (3), 453-463, DOI: 10.1111/j.1474-919x.2005.00440.x.

- [48] O’Neill K.M., Fultz J.E., Ivie M.A. (2008). Distribution of adult Cerambycidae and Buprestidae (Coleoptera) in a subalpine forest under shelterwood management. The Coleopterists Bulletin, 62 (1), 27-36.

- [49] Sakalian V., Langourov M. (2004). Colour traps a method for distributional and ecological investigations of Buprestidae (Coleoptera). Acta Societatis Zoologicae Bohemicae 68, 53-59.

- [50] Klausnitzer B., Klausnitzer U., Wachmann E. et al. (2016). Die Bockkäfer Mitteleuropas. VerlagsKG Wolf, Magdeburg, Germany, here pp. 118-133.

- [51] Földesi R., Kovács-Hostyánszki A., Korösi A. et al. (2016). Relationships between wild bees, hoverflies and pollination success in apple orchards with different landscape contexts. Agricultural and Forest Entomology 18 (1), 68-75, DOI: 10.1111/afe.12135.

- [52] Roquer-Beni L., Alins G., Arnan X., et al. (2021). Management-dependent effects of pollinator functional diversity on apple pollination services: A response-effect trait approach. Journal of Applied Ecology 58 (12), 2843-2853, DOI: 10.1111/1365-2664.14022.

- [53] Ahrné K., Bengtsson J., Elmqvist T. (2009). Bumble Bees (Bombus spp) along a gradient of increasing urbanization. PLoS One 4:e5574, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005574.

- [54] Kuppler J., Neumüller U, Mayr A.V. et al. (2023). Favourite plants of wild bees. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 342:108266, DOI: 10.1016/j.agee.2022.108266.

- [55] Schindler M., Diestelhorst O., Härtel S. et al. (2013). Monitoring agricultural ecosystems by using wild bees as environmental indicators. BioRisk 8, 53-71, DOI: 10.3897/biorisk.8.3600.

- [56] Höring T.F. (2014). How aphids find their host plants, and how they don’t. Annals of Applied Biology 165 (1), 3-26, DOI: 10.1111/aab.12142.

- [57] Singh R., Singh G. (2016). Aphids and their biocontrol. In: Omkar (ed.). Ecofriendly Pest Management for Food Security. Academic Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, here pp. 63-108.

- [58] Haddad N.M., Crutsinger G.M., Gross K. et al. (2010). Plant diversity and the stability of food webs. Ecology Letters 14 (1), 42-46, DOI: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01548.x.

- [59] Wan N.-F., Zheng X.-R., Fu L.-W. et al. (2020). Global synthesis of effects of plant species diversity on trophic groups and interactions. Nature Plants 6 (5), 503-510, DOI: 10.1038/s41477-020-0654-y.

- [60] Dassou A.G., Tixier P. (2016). Response of pest control by generalist predators to local-scale plant diversity. A meta-analysis. Ecology and Evolution 6 (4), 1143-1153, DOI: 10.1002/ece3.1917.

- [61] Martin E.A., Dainese M., Clough Y., et al. (2019). The interplay of landscape composition and configuration. New pathways to manage functional biodiversity and agroecosystem services across Europe. Ecology Letters, 22 (7), 1083-1094, DOI: 10.1111/ele.13265.

- [62] Tscharntke T., Grass I., Wanger T.C. et al. (2021). Beyond organic farming. Harnessing biodiversity-friendly landscapes. Trend in Ecology and Evolution 36 (10), 919-930, DOI: 10.1016/j.tree.2021.06.010.

- [63] Cramp S., Simmons A.D., Perrins C.M. (1994). Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. The Birds of the Western Palaearctic. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, here pp. 54, 288.